In the course of researching my next novel (and how I love the fact I don’t have to think up new hooks for these articles) I came across Robert M. Price’s The Paperback Apocalypse, a wonderfully thorough overview of fundamentalist End Times literature. Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins’ Left Behind series is neither the first nor the most interesting entry in the field, which has a long and storied history. Left Behind only did for Apocalypse novels what Straight Outta Compton did for Gangsta Rap, propelling the sub-genre into national prominence. The Paperback Apocalypse functions as a road map through this Tribulation territory, with Mr. Price, a professor of scriptural studies at Johnnie Coleman Theological Seminary, as our ecumenical tour guide.

Our Humble Author doesn’t skimp on this trip, making sure to take the scenic route. We begin with genesis—the god Yahweh’s genesis in the moral power struggle between priests and prophets in fifth century Israel. Once an ass-kicking, plague-bringing, god of kingship and nationhood, Yahweh El Elyon morphed into his more-familiar, judgmental self after the Babylonian Exile. With Israel’s upper classes carted off whole hog, the laypeople were (ahem) left behind to puzzle out what the hell could’ve happened. How could their mighty God desert them so callously?

A quick glance at the lives of the prophets provided what we now call the Deuteronomic answer: Israel and Judah’s sins caused God to withdraw His favor. Surprise: it was all King David’s fault. His Royal Highness’ wandering penis had condemned the whole nation. Even if the priests and kings returned (as they would, relatively soon, with the support of Persia’s self-deifying emperor) it could all happen again the next time someone in high office violated the covenant. Better to believe that, someday soon, God would flex his warrior-king muscles and upend the whole status quo, returning to cast the priests into Gahenna. With God dwelling among them, Israel would become a land of priestly people, with all the world’s pagan kings reduced to servile servants of the restored Temple.

Meanwhile, the returning priestly aristocrats did what aristocrats like to do and cracked down on the people’s ad hoc worship. From Persia they brought with them a view of the world we now call Manichean, though back then it was simply Zoroastrian. A Persian prophet and (alleged) contemporary of Moses, Zoroaster taught that all the world’s a battleground between the forces of Good, represented by the god Ahura Mazada and Evil, represented by the antigod Ahriman. Balanced but not equal, Good would surely win out in the end, but until then every human deed, and every historical event, was a proxy battle in their Great War, its outcome a point for one side or the other.

Put these two beliefs together and you’ve got fertile ground to grow yourself a Revelation. Ground lain, Price devotes chapters two through six to an almost-exhaustive dissection of the modern fundamentalist Apocalypse. “Messianic Prophecy”; “The Gospel of the Anti-Christ”; “The Second Coming”; “The Secret Rapture”; all receive point-by-point, Scriptural refutation from our author, who swings a mighty big theological pipe. Actually, he’s Dr. Price, a fact I had to find on the Internet, despite his receiving the degree (in systematic theology from Drew University) twenty-six years before writing this book. Do I smell false modesty? Or is Dr. Price preemptively dodging the anti-intellectual arrows fundamentalists so-love to throw at anyone who questions their beliefs?

Price confesses a personal interest in Apocalyptic literature (calling it a “guilty pleasure” the same words we around this corner of the internet use to defend our love for Bad Movies) but never once mentions his own falling-out with fundamentalism. This isn’t about him; it’s about the indefensibility of modern fundamentalist beliefs. Price (rightly) identifies the “faith” of the Rapture Ready as a collection of half-baked misinterpretations, compounded by willful ignorance of the very Bible they claim to idolize. Like a certain Golden Calf I know, their doctrine breaks under the weight of all these scriptural quotations, from Isaiah to Revelations, which Price helpfully restores to their historical and cultural context, something beyond the keen your average, jumped-up, Southern Baptist.

With a firm grounding in the genre’s “classics,” Price jumps to the early twentieth century, and the first End Times novels. Given the fundamentalist condemnation of novel-reading as a sinful, worldly pursuit—like drinking, whoring, and card playing—its no surprise the first real entry in the genre comes in 1905, with Joseph Birbeck Burroughs’ Titan, Son of Saturn: The Coming World Emperor - A Story of the Other Christ. Now if that’s not a rip-roaring, full-throated, modernist title, I don’t know what is. Can’t you just picture Henry James off to the side, clucking his tongue at it?

From thence we move straight on ‘til morning—past Left Behind (which, fittingly, receives its own chapter at the very end) and right up to more-modern, less-successful, and (believe it or not) less-well-written entries in the genre. Raise your hand if you’ve heard of Hal Lindsey’s Blood Moon. Or William A. Stanmeyer’s Catholic-toned Day of Iniquity: A Prophetic Novel of the End Times. Or James BeauSeigneur’s Christ Clone Trilogy. Or Pat Robertson’s own entry, The End of the Age.

If you have, by now you’re probably pretty pissed at my flippant dismissal of your faith. (I invite you to utilize the Comments button below, and please don’t hesitate to describe the yawning torments of hell awaiting me in the Next World.) If you haven’t heard of these books you probably don’t care, except in an academic sense—marveling at the genre from a distance. Like most speculative fiction (call it “mainstream” as Price does when he reviews "mainstream" Apocalypse novels, like The Stand), fundamentalist End Times novels are the center of a multibillion dollar, international media industry, with more published every year. More, certainly, than anyone could read in a lifetime devoted to the subject.

Thankfully, Dr. Price reads these things for fun, and presents this book as a gift to us. Half-Biblical exegesis, half-book review anthology, The Paperback Apocalypse is just the ticket if you’d like a superficial knowledge of the genre and a thorough knowledge of how to refute its theological underpinnings. Unlike Dr. Price, I make no bones about my personal stake in both projects.

Saturday, May 23, 2009

Sunday, May 17, 2009

Thursday, May 07, 2009

New Review

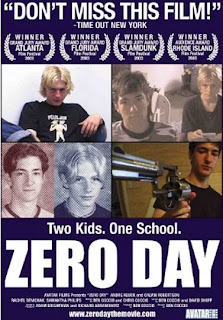

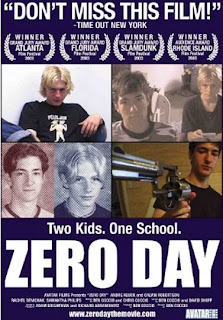

Though I missed the true anniversary of Columbine (April 20th--ten years baby), I offer up this review of Zero Day as my own private observance.

Wednesday, May 06, 2009

Morning News

And now the news. It must be Wednesday.

First, a headline that speaks for itself, so much so you won't see anything like it on this side of the pond: U.S. air strikes kill dozens of Afghan civilians.

And while we're at it, here's an article from last year which vindicates decades of American culture warrior paranoia. Turns out I've been wrong all these years and violent video dogames inspire violence in children...provided those children join the military.

There's a lot of messy connective tissue running between these two articles. Neither acknowledges the fact that, as war becomes more depersonalized, with cause further and further removed from consequence, we're going to have to get used to these civilian casualties. In a strange way we already are. We deny them (literally: see last August's raid on the village of Azizabad) but, since we supplied them, that only make sense. Our military's had a long, tawdry love affair with "strategic" bombing, consummated during World War II. Either we'll continue to shut our eyes to true cost of this poisonous, codependent relationship, or at last reach a point where we can no longer put up with with the overwhelming amounts of bullshit involved.

We are, as a nation, not quite there yet. We'll see how long it takes this "Long War" (oh, I'm sorry, "Overseas Contingency Operation") to break through our national self-denial.

Last note: Minion of the Long War by C.G. Estabrook.

First, a headline that speaks for itself, so much so you won't see anything like it on this side of the pond: U.S. air strikes kill dozens of Afghan civilians.

The police chief Watandar said Taliban guerrillas had herded civilians into houses in the villages of Geraani and Ganj Abad, and these places were then struck by war planes. "The fighting was going on in another village, but the Taliban escaped to these two villages, where they used people as human shields. The air strikes killed about 120 civilians and destroyed 17 houses," he said, admitting, however, that the death toll was imprecise.

And while we're at it, here's an article from last year which vindicates decades of American culture warrior paranoia. Turns out I've been wrong all these years and violent video dogames inspire violence in children...provided those children join the military.

Fancy yourself as a tasty videogamer? [That's what my girlfriend tells me.--D] Then you might soon want to pursue a career in the army. Joypad dexterity, that most 21st-century of skills, is poised to assume a key role on the battlegrounds of Afghanistan and Iraq, now that defense contractor Raytheon has announced plans to use videogame technology in its unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones.

There's a lot of messy connective tissue running between these two articles. Neither acknowledges the fact that, as war becomes more depersonalized, with cause further and further removed from consequence, we're going to have to get used to these civilian casualties. In a strange way we already are. We deny them (literally: see last August's raid on the village of Azizabad) but, since we supplied them, that only make sense. Our military's had a long, tawdry love affair with "strategic" bombing, consummated during World War II. Either we'll continue to shut our eyes to true cost of this poisonous, codependent relationship, or at last reach a point where we can no longer put up with with the overwhelming amounts of bullshit involved.

We are, as a nation, not quite there yet. We'll see how long it takes this "Long War" (oh, I'm sorry, "Overseas Contingency Operation") to break through our national self-denial.

Last note: Minion of the Long War by C.G. Estabrook.

Sunday, May 03, 2009

As the World Burns (And Encouraging Message of Hope from Your Humble Narrator)

Much as I despise the American Empire, I live here too, in the heart of a major American city I’d just as soon not see reduced to a cloud of ash.

Yet it is inevitable. Someone, at some point, will acquire the Bomb and use it, a fact previous generations understood. Visions of nuclear apocalypse are less popular now, with the Cold War a distant memory and the Terror War fast receding into the black hole at the heart of American national memory. Still, they do have their own, sick utility, insomuch as they inspire personal, national and international efforts to put the genii back in the bottle. A foolish dream, perhaps, and hard to hold in an era where non-martial dreams are ridiculed and despised, but it’s mine, nevertheless.

Others dream of phantom enemies. In a report released two weeks ago, as open, armed conflict resumed across northern Pakistan, David Albright—that is Dr David Albright, president and founder of the Institute for Science and International Security—warned “the public” (which, according to my handy English-to-Think Thank-ese dictionary, means “Congress”) that “the security of any nuclear material” produced by Pakistan’s ever-increasing number of nuclear reactors “is in question.”

It’s not enough that al Qaeda-allied crazy folks are sixty miles from the capital. It’s not enough that the Pakistani military is, even now, bombing the northwestern portions of its own country back into the Precambrian Age. It’s not enough that this violence has displaced millions, killed thousands, and enraged untold multitudes who won’t hesitate for a moment to join up with the next charismatic asshat who comes riding over the mountainous border, intent on recruiting fresh martyrs to the cause. No. They have to have dirty bombs, too.

From The Power of Nightmares:

Yet it is inevitable. Someone, at some point, will acquire the Bomb and use it, a fact previous generations understood. Visions of nuclear apocalypse are less popular now, with the Cold War a distant memory and the Terror War fast receding into the black hole at the heart of American national memory. Still, they do have their own, sick utility, insomuch as they inspire personal, national and international efforts to put the genii back in the bottle. A foolish dream, perhaps, and hard to hold in an era where non-martial dreams are ridiculed and despised, but it’s mine, nevertheless.

Others dream of phantom enemies. In a report released two weeks ago, as open, armed conflict resumed across northern Pakistan, David Albright—that is Dr David Albright, president and founder of the Institute for Science and International Security—warned “the public” (which, according to my handy English-to-Think Thank-ese dictionary, means “Congress”) that “the security of any nuclear material” produced by Pakistan’s ever-increasing number of nuclear reactors “is in question.”

It’s not enough that al Qaeda-allied crazy folks are sixty miles from the capital. It’s not enough that the Pakistani military is, even now, bombing the northwestern portions of its own country back into the Precambrian Age. It’s not enough that this violence has displaced millions, killed thousands, and enraged untold multitudes who won’t hesitate for a moment to join up with the next charismatic asshat who comes riding over the mountainous border, intent on recruiting fresh martyrs to the cause. No. They have to have dirty bombs, too.

From The Power of Nightmares:

Saturday, May 02, 2009

Book Review: Kids Who Kill by Charles Patrick Ewing

I’m toying with the idea of turning this blog into research journal for the last two months, rolling it around in my mind the way you’d roll an unwanted interloper in feathers after dousing him with honey, or hot tar. The old injunction, “Write what you know,” is a challenge, not a straightjacket. The implicit corollary, “Learn more and you’ll be able to write more,” is my engine, driving a lifetime of education in subjects most schools would rather not touch. Like school shaootings.

In the course of researching my next novel (which is one of those wonderful sentences writers get to write, the kind that just glow at you) I’ve learned a lot about school shootings. Except that’s not exactly accurate. I’ve remembered a good ninety-eight percent of the more memorable stuff, since it began right around the time I began to pay attention to the world outside the bounds of my small, Midwestern town. The ten-year anniversary of Columbine (which I allowed to pass unnoticed) helped me tremendously in this. Time magazine even resurrected it’s deliciously sensationalist article on the subject from December, 1999, reheating the case’s particular blend of hash.

The Portland Community College library provided me two not-so-excellent books on the subject this week. Published ten years apart, they nicely bookend that extraordinary heyday of youth-perpetrated violence still blithely refer to as, “the 90s.”

One end, Charles Patrick Ewing’s Kids Who Kill, rests in 1989. Despite the copyright date (1990), Kids Who Kill is an unabashed product of the 1980s, filled with lucid accounts of heinous “juvenile” crimes, subdivided into chapter-length categories. Its chapter titles read like prime time, news-magazine show bumpers: “Family Killings,” “Senseless Killings,” “Cult-Related Killings,” “Gang Killings,” “Little Kids Who Kill,” and my personal favorite, the nebulous “Crazy Killings.”

Author Ewing is an all-but-invisible presence through all this, filling each chapter with capsule descriptions of theme-specific cases, drawn from the best mainstream media sources of his time: the Boston Globe, the Chicago Tribune, UPI, the New York and Los Angeles Times. A source citation page totally devoid of web addresses is a strange artifact to find, from another, alien time…much like the book itself. Ewing’s tone is equally foreign to those of us on the other side of the great Faux News divide. After a decade and a half of personalized news, delivered unto us by news personalities (celebrity anchors, talking heads, snakeoil information salesmen, pundits), Ewing’s case studies seem fleeting, callous, bite sized examinations of events that garner round-the-clock, team coverage these days, and passed unnoticed in a world just coming to grips with the end of the Cold War and the dawning of our current New World Order. A typical entry, chosen at random, reads like the ticker at the bottom of your TV screen.

Another example:

And so long as I’ve Fair Use on my side, have one more:

One hundred seventy pages of this is enough to make you take a bite out of capital-C, Crime, whilst simultaneously saying, "No" to the drugs and fantasy role playing games that are destroying our nation’s youth.

If the past is another country, writers must be anthropologists. A good anthropologist will take heed of a culture’s fears and superstitions. Kids Who Kill suggests that a peculiar fear of youth slumbers at the heart of our culture, occasionally rearing its head to freeze us with a Cobra gaze straight out of Rudyard Kipling. It rose up in 1990, and again in 1999, events building upon themselves, sprouting intertwining threads of correspondence and coincidence.

None of which has anything to do with Kids Who Kill, which is a strange, haunting little book that, in its final pages, suggests four commonsensical “known factors” common to killer kid cases: “child abuse, poverty, substance abuse, and access to guns.” School shooters of the now-familiar type (spree-killing monsters in black coats stuffed full of weapons) lying downstream from Ewing in the course of history, go unexamined. History responds in kind by refusing to vindicate the dire predictions Ewing puts forth in lieu of conclusion in his final chapter, “Juvenile Crime in the 1990s.”

There, Ewing predicts that juvenile homicides will reach “record high proportions” by the year 2000, ignorant of the fact juvenile homicide as a whole would peak in the recession years of 1992-3, years of riot and tumult, when American nonchalantly joked about being broke. (A bit like now, come to think about it…) Ewing leaves himself little time to flesh out his “known factors” or do anything more than refer back to a few previously described cases by way of illustration. There’s little analysis here (besides a few tables), and no discernible political agenda. When this book saw print the culture wars that drive (and define) today’s non-fiction publishing industry were barely a glimmer in Rush Limbaugh’s eye. If our wider, societal obsession with vicarious violence bares any blame for creating killer kids, Ewing does not say. Instead, he reminds us that Ronald Regan’s eight year “war on the poor” sure as shit didn’t help. Matter of fact (Ewing says, in his own detached, Joe-Friday, just-the-facts-ma’am way), Reganomics did plenty to exacerbate the four “known factors,” factors ignored and/or exacerbated by the then-current administration of George (HW) Bush.

Busy building a New World Order, America would go on to largely ignore Ewing’s slim little book, or its dire warnings for the future. Each of his four “known factors” remained in operation, resurfacing ten years later in the Great Explosion of school shooting and killer kid literature of 1996-9…some of which we’ll turn to next time, as our research into this negative image of the American dream continues.

Note: Special thanks to Anonymous for catching my Freudian slip involving the author's name. I was thinking of earwigs.

In the course of researching my next novel (which is one of those wonderful sentences writers get to write, the kind that just glow at you) I’ve learned a lot about school shootings. Except that’s not exactly accurate. I’ve remembered a good ninety-eight percent of the more memorable stuff, since it began right around the time I began to pay attention to the world outside the bounds of my small, Midwestern town. The ten-year anniversary of Columbine (which I allowed to pass unnoticed) helped me tremendously in this. Time magazine even resurrected it’s deliciously sensationalist article on the subject from December, 1999, reheating the case’s particular blend of hash.

The Portland Community College library provided me two not-so-excellent books on the subject this week. Published ten years apart, they nicely bookend that extraordinary heyday of youth-perpetrated violence still blithely refer to as, “the 90s.”

One end, Charles Patrick Ewing’s Kids Who Kill, rests in 1989. Despite the copyright date (1990), Kids Who Kill is an unabashed product of the 1980s, filled with lucid accounts of heinous “juvenile” crimes, subdivided into chapter-length categories. Its chapter titles read like prime time, news-magazine show bumpers: “Family Killings,” “Senseless Killings,” “Cult-Related Killings,” “Gang Killings,” “Little Kids Who Kill,” and my personal favorite, the nebulous “Crazy Killings.”

Author Ewing is an all-but-invisible presence through all this, filling each chapter with capsule descriptions of theme-specific cases, drawn from the best mainstream media sources of his time: the Boston Globe, the Chicago Tribune, UPI, the New York and Los Angeles Times. A source citation page totally devoid of web addresses is a strange artifact to find, from another, alien time…much like the book itself. Ewing’s tone is equally foreign to those of us on the other side of the great Faux News divide. After a decade and a half of personalized news, delivered unto us by news personalities (celebrity anchors, talking heads, snakeoil information salesmen, pundits), Ewing’s case studies seem fleeting, callous, bite sized examinations of events that garner round-the-clock, team coverage these days, and passed unnoticed in a world just coming to grips with the end of the Cold War and the dawning of our current New World Order. A typical entry, chosen at random, reads like the ticker at the bottom of your TV screen.

[F]our New Jersey youths—members of a much larger, self-proclaimed group of “Dotbusters”—beat a thirty-year-old Indian man to death in a city street. According to the police, these “Dotbusters”—who took their name from the red bindi mark worn on the foreheads of married Indian women—were responsible for numerous violent attacks against Indian and Pakistani immigrants. The youths in this particular case, who ranged in age from fifteen to seventeen, denied any racial motive for their brutal attack. Instead, they insisted that they attacked the Indian man because he was bald. Though charged with murder, they were convicted only of assault.

Another example:

On July 10, 1989 a fourteen-year-old Chicago mother was trying to watch television. After being interrupted several times by her one-month-old son who would not stop crying, the girl smothered the infant with a disposable diaper. The teenager was charged with murder, but a judge ruled that given her “previously clean record” she would not be tried as an adult.

And so long as I’ve Fair Use on my side, have one more:

In January 1988, seventeen-year-old Leslie Torres, a homeless New York City youth, went on a seven day “cocaine-inspired rampage”—a spree of armed robberies in which he killed five people and wounded six others. When arrested, Leslie told police that he committed numerous killings and robberies to support his $500-a-day addiction to the street drug [sic], crack. Charged with murder, he pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity.

Testifying on his own behalf, Leslie told jurors that crack caused him to eel like God, but that he saw the Devil whenever he looked in the mirror. After examining Leslie, a psychiatrist testified that the teenager suffered from “cocaine induced psychosis” at the time o the robberies and killings. The jury rejected Leslie’s insanity defense and convicted him of murder. Finding that the seventeen-year-old “showed utter and total disregard for the sanctity of life” and “would kill again” if ever released, a judged sentenced Leslie Torres to sixty years to life in prison.

One hundred seventy pages of this is enough to make you take a bite out of capital-C, Crime, whilst simultaneously saying, "No" to the drugs and fantasy role playing games that are destroying our nation’s youth.

If the past is another country, writers must be anthropologists. A good anthropologist will take heed of a culture’s fears and superstitions. Kids Who Kill suggests that a peculiar fear of youth slumbers at the heart of our culture, occasionally rearing its head to freeze us with a Cobra gaze straight out of Rudyard Kipling. It rose up in 1990, and again in 1999, events building upon themselves, sprouting intertwining threads of correspondence and coincidence.

None of which has anything to do with Kids Who Kill, which is a strange, haunting little book that, in its final pages, suggests four commonsensical “known factors” common to killer kid cases: “child abuse, poverty, substance abuse, and access to guns.” School shooters of the now-familiar type (spree-killing monsters in black coats stuffed full of weapons) lying downstream from Ewing in the course of history, go unexamined. History responds in kind by refusing to vindicate the dire predictions Ewing puts forth in lieu of conclusion in his final chapter, “Juvenile Crime in the 1990s.”

There, Ewing predicts that juvenile homicides will reach “record high proportions” by the year 2000, ignorant of the fact juvenile homicide as a whole would peak in the recession years of 1992-3, years of riot and tumult, when American nonchalantly joked about being broke. (A bit like now, come to think about it…) Ewing leaves himself little time to flesh out his “known factors” or do anything more than refer back to a few previously described cases by way of illustration. There’s little analysis here (besides a few tables), and no discernible political agenda. When this book saw print the culture wars that drive (and define) today’s non-fiction publishing industry were barely a glimmer in Rush Limbaugh’s eye. If our wider, societal obsession with vicarious violence bares any blame for creating killer kids, Ewing does not say. Instead, he reminds us that Ronald Regan’s eight year “war on the poor” sure as shit didn’t help. Matter of fact (Ewing says, in his own detached, Joe-Friday, just-the-facts-ma’am way), Reganomics did plenty to exacerbate the four “known factors,” factors ignored and/or exacerbated by the then-current administration of George (HW) Bush.

Busy building a New World Order, America would go on to largely ignore Ewing’s slim little book, or its dire warnings for the future. Each of his four “known factors” remained in operation, resurfacing ten years later in the Great Explosion of school shooting and killer kid literature of 1996-9…some of which we’ll turn to next time, as our research into this negative image of the American dream continues.

Note: Special thanks to Anonymous for catching my Freudian slip involving the author's name. I was thinking of earwigs.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)